A Website is a Machine for Information and Delight

Increasingly, we are inundated with imagery aimed at directing our behavior. As available data increases, design patterns are developed and market competition becomes more steep, we risk having this flood of content overwhelm the consumers of digital media, leaving particularly vulnerable the youth who have not known a world without the internet and, also, have not yet developed parts of their brain responsible for inhibition and self-control. As designers, we have a moral obligation to consider the broader context in which we are creating and the history of design trends so that we can make more ethical decisions while creating digital media.

Like a hammer, a wheel or any other machine, websites can be used for many purposes, but it is up to us to reject uses that can be harmful to society and instead create websites that are both useful and delightful.

Le Corbusier & Brutalism in the age of Digital Design

In the early 20th century, Modernism became the dominant architectural movement in Europe. Inspired by the Modernist principle of "form follows function," architects sought to create buildings that embodied the ideals of utilitarianism, egalitarianism, and honesty, eschewing the elaborate ornamentation customary in classical architecture.

The radical shift towards functionality seen in the Modernist movement was pushed to an extreme by Le Corbusier, the influential Swiss-French architect and urban planner, who, under the banner of Brutalism, famously argued that a house is a machine for living in. In line with this utilitarian approach, and against the backdrop of WWII reconstruction, architects of the day turned towards Béton Brut — the French term for Raw Concrete — as their material of choice for rebuilding a war-torn Europe. Le Corbusier's vision was brought to life with his seminal work Unite d'Habitation, an imposing concrete housing complex built in Marseille, France, and completed in 1952, introducing to the world an architectural framework with the potential to address some of the world's most pressing social issues.

While both Modernism and Brutalism allowed architects to discard certain historical baggage, they inevitably became constrained by new historical factors. This time, these constraints were associated with a quickly changing, increasingly global, and deeply tumultuous world shaken by conflict and social strife.

The Dark Side of Brutalism

On the surface, Brutalism championed a pragmatic approach to the construction of housing and infrastructure. From a more nuanced perspective, however, it was a response to the lightness of Modernism. Yet, on a deeper level still, its aesthetic presentation was, consciously or subconsciously, animated by the horrors of WWII and the emerging power struggle between the West and the Soviet Union.

As governments, and the world, became more dependent on automation and computerization, the importance of data, logistics and efficiency increasingly overshadowed the more familiar and human-centric ways of life that many were used to. Brutalist buildings, then, made of raw concrete and devoid of visible humanistic considerations, were monuments to those changing times, giving shape to a reality that was otherwise nebulous, difficult to grasp, yet deeply troubling.

Translating Brutalism in the Digital Era

Brutalism in digital design has become a popular aesthetic trend in recent years. However, it has evolved in a way that is detached from the depth and significance of its original critique. With this new form of Brutalism, we no longer see the traditional lack of ornamentation or the use of raw materials, ie the display of code; instead, we encounter excessive ornamentation, bright colors, and unnecessary animations — the veneer of Austerity and rawness covering over rampant consumerism in present-day digital media.

This deviation not only represents a step back for Brutalism but contrasts with Modernist principles, as well. As Alfred Loos's argues in his 1908 essay Ornament and Crime,

the evolution of culture marches with the elimination of ornament from useful objects.

With the vast majority of digital media essentially serving as ornament, we must ask, is the Brutalist framework — in the age of mass consumption — truly capable of serving this medium or does digital media currently simply absorb and re-present all aesthetics for an end-user in search of 'content'?

The above line of questioning opens two possible avenues for exploration: the first with regard to Guy Debord's concept of the the Spectacle and, the second, concerning the French Psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan's 'object petit a', both of which will be explored in a future post.

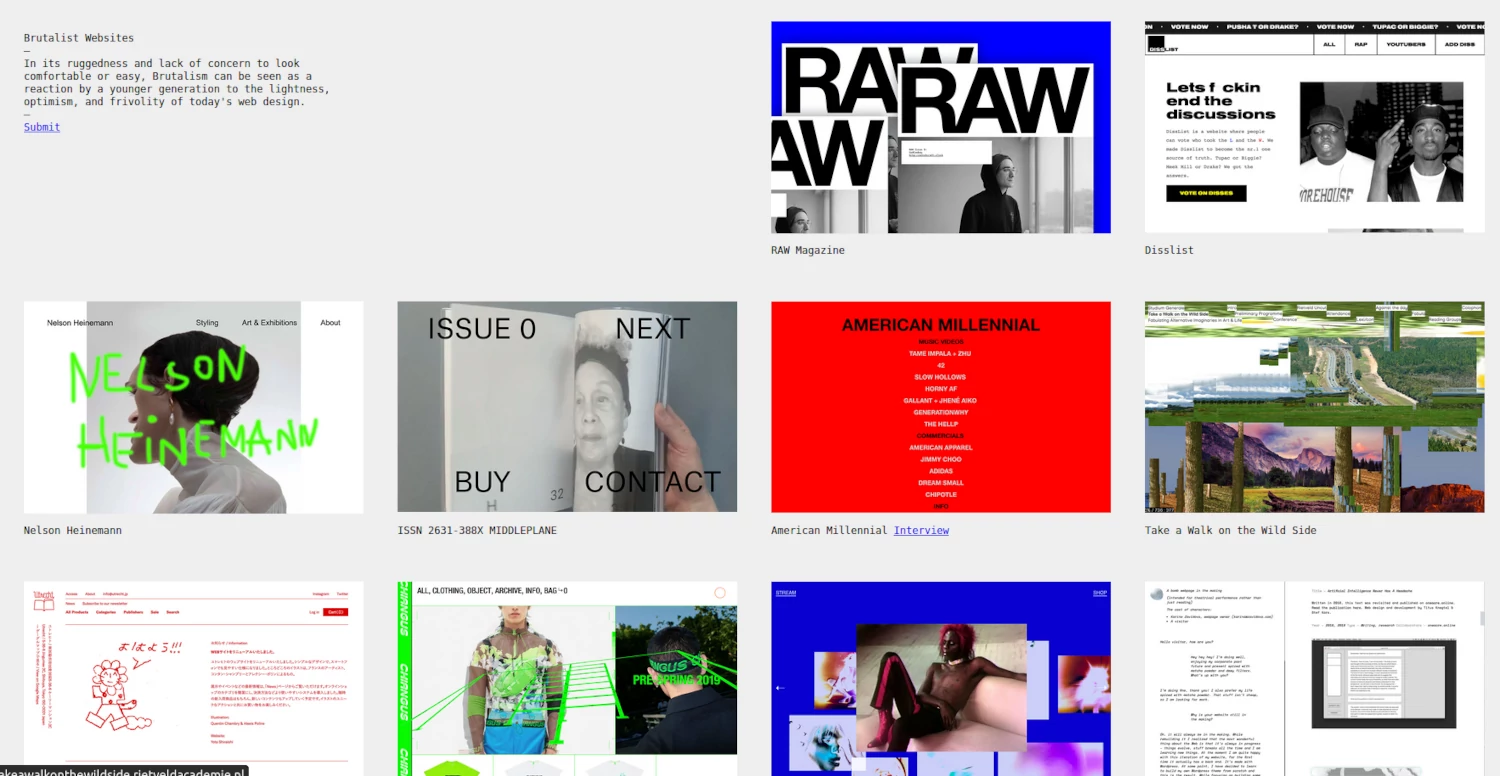

To better understand contemporary Brutalism, we can look at the definition presented on the website brutalistwebsites.com:

In its ruggedness and lack of concern to look comfortable or easy, Brutalism can be seen as a reaction by a younger generation to the lightness, optimism, and frivolity of today's web design.

In this context, Brutalism is said to provide a counter-weight to the alleged "frivolity" of certain web design, but, for the reasons described above, it seems to be more of a simple flip-side, substituting superficial ease with superficial difficulty, never diving into an actual critique as was the case with Brutalism's original appearance.

Therefore, if we had to categorize Brutalist websites in a taxonomy of digital media, while they might be interesting, jarring and appear novel, we cannot yet say they are fundamentally different from more pleasant looking websites.

Despite the difficulties of creating meaning in world saturated with fleeting imagery, designers might desire to pierce the surface-level aesthetic to create websites in a more intentional way in order to hold true to the principle of "form follows function".

"Ex Machina" home — AI meets Brutalism in film.

Making Websites That Delight

If, according to Le Corbusier, a home is a machine for living in, then how shall we understand websites, given the Brutalist framework?

They are indeed machines for information but, is that all?

Whereas the primary function of a home is to provide shelter, a fundamental human need, websites serve a variety of purposes. They are used to document, for commerce, to communicate news and events, for politics, and sometimes simply for fun. Though catering to all needs is unattainable, if user engagement is the objective, there are multiple paths to take. Some strategies may employ dark patterns or attention manipulation techniques, designed to unfairly direct user behavior; however, delighting the user remains the most ethical method, fostering genuine engagement and trust.

Keeping this in mind, we can refer to Dieter Rams' "Ten Principles for Good Design" as a guide:

- Good design is innovative: It doesn't merely replicate existing designs but strives to offer new solutions.

- Good design makes a product useful: It prioritizes the product's usability over its aesthetics.

- Good design is aesthetic: Despite the emphasis on usability, good design should also be visually appealing.

- Good design makes a product understandable: It clarifies the product's structure and operation.

- Good design is unobtrusive: Design should be neutral, providing room for the user's self-expression.

- Good design is honest: It doesn't make promises that the product can't fulfil.

- Good design is long-lasting: It avoids trends and thus never seems out of date.

- Good design is thorough down to the last detail: Nothing is arbitrary or left to chance.

- Good design is environmentally-friendly: It conserves resources and minimizes physical and visual pollution.

- Good design is as little design as possible: It focuses on the essential aspects of a product and eliminates the superfluous.

Following these 10 Principles, designers can create websites that not only fulfill a functional role but also deliver a delightful and ethical user experience, aligning with the values of both aesthetics and responsibility.

The Enduring Appeal of Modernism and Brutalism

In the midst of a world overrun with imagery, the principles of Modernism and Brutalism offer distinct perspectives and challenges. Modernism, with its minimalism and focus on essential design aspects, continues to provide a timeless and relevant aesthetic across various disciplines. Brutalism, though not perfect, its stripped-down stark forms, resonates with those seeking authenticity and a reaction against superficiality. As designers continue to navigate this complex landscape, the enduring lessons of both Modernism and Brutalism serve as valuable guides, paving a path forward that honors both aesthetics and ethical responsibility, and echoes the timeless mantra that 'form follows function.'